Bygones -A Stirring Reflection on Legacy, Loyalty, and the Healing Power of Forgiveness

Directed by Angel McCoughtry, 'Bygones' is an emotionally stirring short film ...

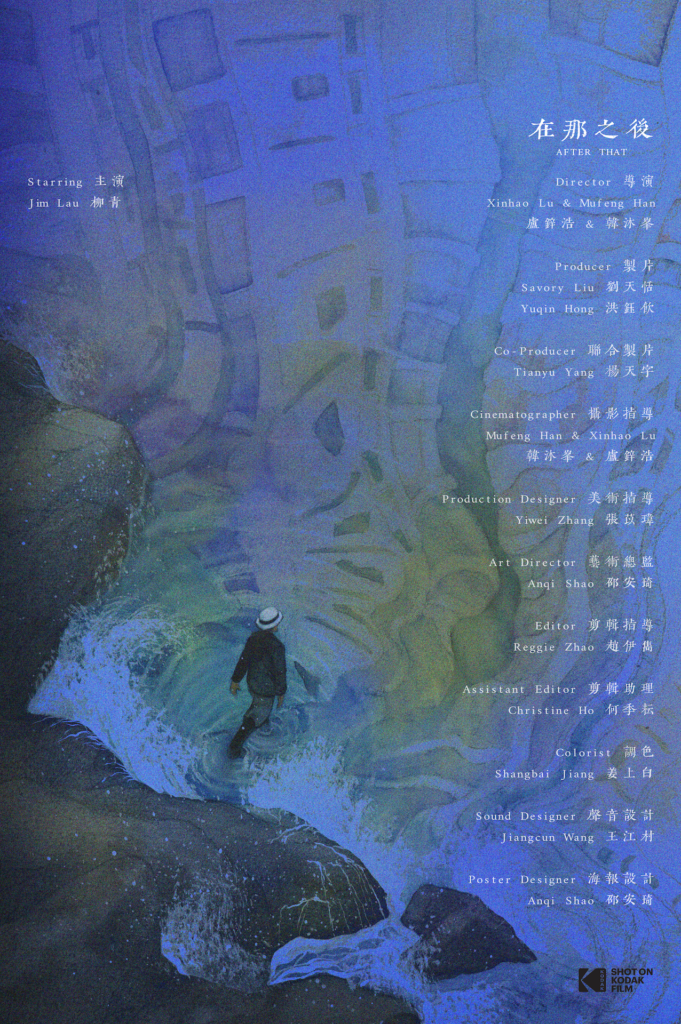

For producer Savory Liu, filmmaking is not just a profession. It has become a lived negotiation between countries, languages, friendships, and quiet anxieties. With over a decade of experience spanning documentary, commercial productions, and larger studio sets in Los Angeles, Liu brings both logistical precision and emotional sensitivity to her work. In ‘After That’, a Super 8mm “video poetry” about displacement and geopolitical unease, she helps translate a deeply personal vision into something intimate yet universal.

Savory: I studied theater and minored in film in college. And I started making documentary films after grad school. Later I was producing some commercials, and had some chances working on bigger budget features and netflix sets. I’ve been producing more commercialized film projects in LA, and After that was the first short film that I produced in LA. I’ve been in this field for over 10 years, and I love working on film sets, being with different people, and learning everyday.

Savory: Violet and Mufeng, our director and DP, we are all very close friends. By the time Mufeng was about to leave the States and move back to China, he wanted to shoot something in super 8. We wanted to achieve this as a memory of our friendship and Mufeng’s time in the States. They were brainstorming ideas and it was really fun for me to sit next to them and listen to their ideas. We met up a couple times during the week and Violet had something in his mind that he always wanted to create on screen, which is the ending of the film.

Savory: We all live in anxiety, I sometimes wonder where exactly is that coming from. Maybe it’s because we have been fed with all the information online that we might not be able to justify? Or does it come from peers and relatives? It is a big world and we are only a very small part of it, After That is a little realization about this fact. We are worried, we want to start thinking about this. But ultimately it is a fantasy story, that’s fulfilled with our hope, we want to keep positive.

Savory: Yes, studying and living abroad also add to the sense of displacement and belonging. Living and working in a country that doesn’t speak your native language is very lonely, that’s why I’m very related to After That. Producing internationally means it is a new team every time, I do meet all different people speaking different languages. They have their interesting life, but at the end of the day, there is still that sense of loneliness, because I know I will only be by myself tomorrow.

Film Producer Savory Liu

Savory: It is by far ok, there hasn’t been any issue about operating internationally. The only thing I would complain about is the visa, just a very difficult process that I need to take care of every time I travel.

Savory: I totally agree with the saying of “video poetry”. Production wise, to be very honest, we shot this film in a very casual way. Good thing is we know the locations, so at least we know where we are going everyday. But we ended up not following the script, we were mainly wandering around certain places of the city, where we felt suits the film and pretty, and we restructured the whole film in post. It is indeed risky, and the first cut doesn’t really work, but we took a long time to come up with a new script and came up with a new film that we are all happy about.

Savory: Violet saw Jim play in a short film before, and then he contacted him. Jim read the script and he liked it, so we were shooting around his schedule. It is a very fast decision without any hesitation. Jim indeed is a very professional actor. There is one scene that we deleted in the post but he was half naked fake swimming at a park, we asked if he could do it, and he said yes immediately. I really wanted to add that scene back to the film but Violet said no haha.

Savory: As I mentioned in the previous question, Jim is a very professional actor, he’s been in this industry over decades. It was my first time meeting him and I think it’s him giving us a sense of security. He was wandering around the city with us, looking for the best scenery and angle. We were chatting like friends, discussing our understanding of the film. I guess in the sense of Chinese Americans living in LA, we all felt the same.

Savory: The locations we choose are quite interesting. Those are the locations that Violet came across in LA, and found beautiful and felt homesick even just being there. I agreed with him, and it would be tricky for production. We know it has to be done without following any rules. We did call the hotel and apparently we can’t afford filming there. But we were just four five people with a super 8 in hand, no sound equipment, no props or wardrobe, we looked more like tourists trying to take pictures of their grandpa. We made it really simple and even had lunch at one of the restaurants at the hotel. The rest of the locations are even easier, and the room location was at a ADU studio at a friend’s.

Savory: Violet decided to use super 8mm, a vintage film camera, to shoot a futuristic film. When the edits came out, it did not look anything but vintage, not even a feeling of futurism. But he said that’s what he wanted, I have to say it is really controversial to do something that challenging. What convinced me is why not? Why don’t we try and why can’t we try? We don’t have to follow the stereotype thinking of futurism, maybe in the future when we look back to this film, this is a pioneer.

Savory: Chinese audiences, especially those who understand Cantonese, would definitely resonate with the mood of the whole film better. But the American audience might get a better sense of the geopolitical instability. Whoever speaks Cantonese, has lived abroad, will get the closest complete understanding of the film. The sense of instability, insecurity, homesickness, and maybe just a little bit sad about existing. We wanted to explore the possibility of the future, it is mysterious and anything could happen. So we wanted to let the audience know, this could be the future, and don’t forget about whoever you love.

Savory: Definitely! We’ve collaborated a lot in the commercialized filming world ever since, and I’ve already shot another short film with him back in China last summer. We wish we could do more festival runs and eventually start making features.

Savory: Please keep making films! Creating and writing is difficult, and don’t forget there is always a community. Chat with your filmmaker friends, share your script and ideas, and keep watching films. Sometimes, it is ok to stop, take a break, go do something completely different and talk to people you haven’t talked to for a while, and you will find surprising things!

At its heart, After That feels less like a film engineered for spectacle and more like a fragile time capsule of friendship, of uncertainty, of existing between worlds. For Savory Liu, producing it was an act of trust: in collaboration, in experimentation, and in the belief that cinema can quietly hold our fears without being consumed by them. As she continues building cross-continental partnerships and dreaming toward future features, one thing remains constant. Her faith in community, in persistence, and in the simple but powerful act of continuing to make films, even when the future feels uncertain.

Leave A Reply